The Classic A Christmas Carol – Released in 1843

Most of us can remember the wonderful story that Charles Dickens wrote about the Christmas season, A Christmas Carol. The story presents such memorable characters like the old miser Scrooge, the innocent Tiny Tim, the Struggling Bob Cratchit, Scrooge’s X-Partner – Jacob Marley, the Ghosts of Christmas, among others. The Christmas Carol has been told and retold since it was first introduced the world in 1843. It is undoubtably a Christmas Classic.

Summary

The book is a novella by Charles Dickens, first published in London by Chapman & Hall in 1843 and illustrated by John Leech. The book recounts the story of Ebenezer Scrooge, an elderly miser who is visited by the ghost of his former business partner Jacob Marley and the spirits of Christmas Past, Present and Yet to Come. After their visits, Scrooge is transformed into a kinder, gentler man.

When was it written?

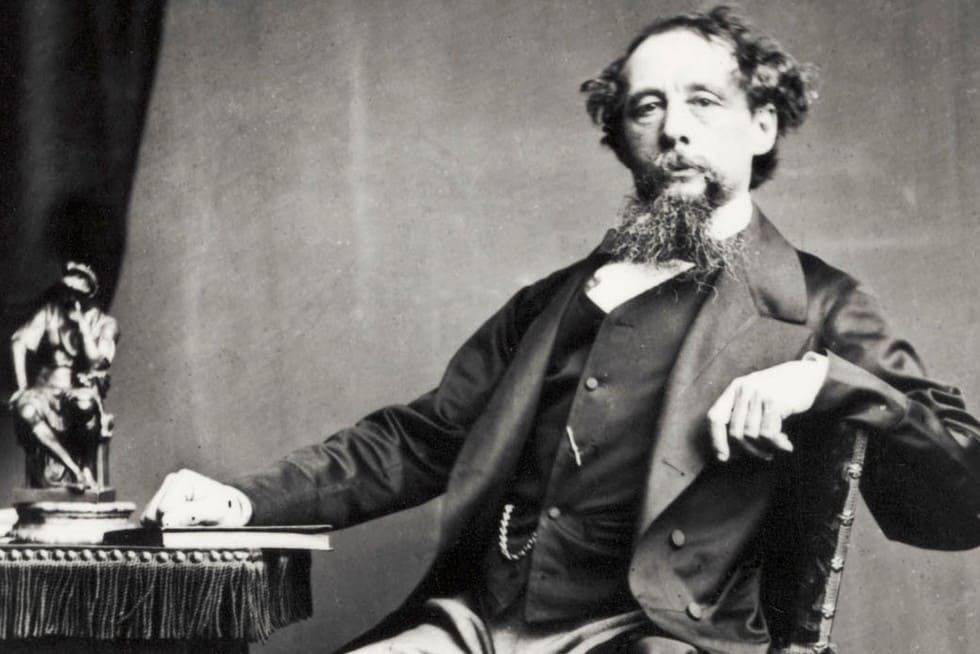

Dickens wrote the book during a period when the British were exploring and re-evaluating past Christmas traditions, including carols, and newer customs such as cards and Christmas trees. He was influenced by the experiences of his own youth and by the Christmas stories of other authors, including Washington Irving and Douglas Jerrold.

A Culmination of Other writings

Dickens had written three Christmas stories prior to the novella, and was inspired following a visit to the Field Lane Ragged School, one of several establishments for London’s street children. The treatment of the poor and the ability of a selfish man to redeem himself by transforming into a more sympathetic character are the key themes of the story. There is discussion among academics as to whether this is a fully secular story, or if it is a Christian allegory.

Publishing Issues

Published on 19 December, the first edition sold out by Christmas Eve; by the end of 1844 thirteen editions had been released. Most critics reviewed the novella favorably. The story was illicitly copied in January 1844; Dickens took legal action against the publishers, who went bankrupt, further reducing Dickens’s small profits from the publication.

Story Translated into Other Medium

He went on to write four other Christmas stories in subsequent years. In 1849 he began public readings of the story, which proved so successful he undertook 127 further performances until 1870, the year of his death. The book has never been out of print and has been translated into several languages; the story has been adapted many times for film, stage, opera and other media.

The story Captures the Victorian Era

The book captured the zeitgeist of the early Victorian revival of the Christmas holiday. Dickens acknowledged the influence of the modern Western observance of Christmas and later inspired several aspects of Christmas, including family gatherings, seasonal food and drink, dancing, games and a festive generosity of spirit.

Legacy

The phrase “Merry Christmas” had been around for many years – the earliest known written use was in a letter in 1534 – but Dickens’s use of the phrase and it is popularized it among the Victorian public. The exclamation “Bah! Humbug!” entered popular use in the English language as a retort to anything sentimental or overly festive; the name “Scrooge” became used as a designation for a miser and was added to the Oxford English Dictionary as such in 1982.

The story Impacted Christmas Celebrations

In the early 19th century, the celebration of Christmas was associated in Britain with the countryside and peasant revels, disconnected to the increasing urbanization and industrialization taking place. Davis considers that in A Christmas Carol, Dickens showed that Christmas could be celebrated in towns and cities, despite increasing modernization.

The modern observance of Christmas in English-speaking countries is largely the result of a Victorian-era revival of the holiday. The Oxford Movement of the 1830s and 1840s had produced a resurgence of the traditional rituals and religious observances associated with Christmastide and, with A Christmas Carol, Dickens captured the zeitgeist while he reflected and reinforced his vision of Christmas.

Dickens Augments Christmas

Dickens advocated a humanitarian focus of the holiday, which influenced several aspects of Christmas that are still celebrated in Western culture, such as family gatherings, seasonal food and drink, dancing, games and a festive generosity of spirit. The historian Ronald Hutton writes that Dickens “linked worship and feasting, within a context of social reconciliation”.

The novelist William Dean Howells, analyzing several of Dickens’s Christmas stories, including A Christmas Carol, considered that by 1891 the “pathos appears false and strained; the humor largely horseplay; the characters theatrical; the joviality pumped; the psychology commonplace; the sociology alone funny”. The writer James Joyce considered that Dickens took a childish approach with the book, producing a gap between the naïve optimism of the story and the realities of life at the time.

Ruth Glancy, the professor of English literature, states that the largest impact of A Christmas Carol was the influence felt by individual readers. In early 1844 The Gentleman’s Magazine attributed a rise of charitable giving in Britain to Dickens’s novella; in 1874, Robert Louis Stevenson, after reading Dickens’s Christmas books, vowed to give generously to those in need, and Thomas Carlyle expressed a generous hospitality by hosting two Christmas dinners after reading the book.

In 1867 one American businessman was so moved by attending a reading that he closed his factory on Christmas Day and sent every employee a turkey, while in the early years of the 20th century Maud of Wales – the Queen of Norway – sent gifts to London’s crippled children signed “With Tiny Tim’s Love”. On the novella, the author G. K. Chesterton wrote “The beauty and blessing of the story … lie in the great furnace of real happiness that glows through Scrooge and everything around him. … Whether the Christmas visions would or would not convert Scrooge, they convert us.”

Analyzing the changes made to adaptations over time, Davis sees changes to the focus of the story and its characters to reflect mainstream thinking of the period. While Dickens’s Victorian audiences would have viewed the tale as a spiritual but secular parable, in the early 20th century it became a children’s story, read by parents who remembered their parents reading it when they were younger. In the lead-up to and during the Great Depression, Davis suggests that while some saw the story as a “denunciation of capitalism, …most read it as a way to escape oppressive economic realities”.

The film versions of the 1930s were different in the UK and US. British-made films showed a traditional telling of the story, while US-made works showed Cratchit in a more central role, escaping the depression caused by European bankers and celebrating what Davis calls “the Christmas of the common man”. In the 1960s, Scrooge was sometimes portrayed as a Freudian figure wrestling with his past. By the 1980s he was again set in a world of depression and economic uncertainty.

To Return to Our Main Christmas Site, Follow This Link…

The All Christmas Website (celebratechristmas.co)