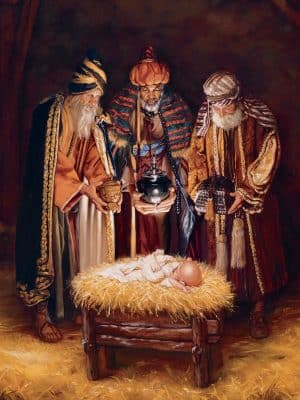

“We Three Kings” tells the story of the wisemen who went to visit baby Jesus the night of his birth.

We Three Kings tells of the Wisemen Who Came to Visit Jesus

In the second chapter of the book of Matthew there is a brief passage that reads, “There came wise men from the east to Jerusalem.” Who were these men? Most, including King Herod, thought they were astrologers. That is how they are identified in the Bible. When they informed Herod they were looking for the “king of the Jews.” It caused panic in the royal court and ultimately led to the murder of countless baby boys throughout the land of Israel in an attempt to kill a future threat.

While Herod struck terror throughout the land in his search for the baby Jesus, the wise men found the child by following a star to Bethlehem. According to the gospel of Matthew, they threw themselves at the infant’s feet and worshiped him, presenting him with gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh. Then, without reporting back to Herod, they departed for home, never to be heard from again.

What many call the commercialization of Christmas – the practice of giving gifts – can probably be traced to the wise men’s presents that very first Christmas. Beyond that fact, nothing else is really known about the wise men. Still, despite a lack of concrete knowledge, a host of writers and theologians have drawn some very detailed pictures of the famous travelers over the past twenty centuries.

Where Did the Three Wise Men Come From?

The consensus of opinion among most serious Bible scholars is that the astrologers came from Persia. The fact that astrologers in the land were often priests is probably why they are often called Magi. The Magi were, in fact, dream interpreters for the Persian royal family. Though they often worked within the confines of the royal palace with the kings of the country, these wise men were not of royal blood and not even members of the ruling caste. So if they were Persian star readers, they could not be kings.

The Wise Men and Their Gifts

How many wise men made the journey to Israel in search of Jesus is another question that has been answered more by imagination than documentation. No one really knows how many there were. Because the text in Matthew clearly records wise “men”, there were obviously at least two. The three wise men so often mentioned in stories and songs probably resulted in the fact that Matthew told of three gifts brought by the wise men to Jesus.

The number of gifts, however, had nothing to do with how many wise men had brought them; the gifts were symbolic of the important three areas of Christ’s life – the gold representing his kingly reign, the frankincense symbolizing his ministry, and the myrrh foreshadowing his death and resurrection. There could have been as few as two wise men or as many as a dozen or more.

Epiphany Tell Now.

Writers of the Middle Ages not only extrapolated about number, but even made “educated guesses” at names. BY 1500 millions of Christians could tell you not only that the three men’s name were Casper, Balthazar, and Melchoir, but also that this trio of gift bearers were actually kings. While from a historical perspective this made little sense, it did add something special to many of the imagined tales that sprang forth over the next four hundred years.

Three kings or not, the story of the wise men was the focal point of the post-Christmas celebration of Epiphany. In many places the holiday, observed on January 6, once rivaled Christmas. Since the celebration of Epiphany has declined over the past century, many today don’t know what it is. Literally, Epiphany is the last of the twelve days of Christmas, the day the wise men finally found Jesus.

The Episcopal Church celebrated Epiphany in both America and the United Kingdom. During the 1800s the special day was traditionally the day the Christmas tree was taken down and children received the gifts and treats that had been hanging on it since it had ben cut, brought home, decorated, and had presents hung on the branches. Even then, as many little ones counted the moments until they could raid the evergreen, a great number of them didn’t know the symbolism behind Epiphany or why gift-giving was a part of it.

Though he had no children of his own, thirty-seven-year-old John Henry Hopkins Jr. enjoyed the childlike spirit of the Christmas season he saw in observing his nephews and nieces. A brilliant scholar, with degrees from the University of Vermont and a law school in New York City, he was still a child at heart. And as an ordained priest in the Episcopal church, he did not wear his clerical collar at the time, favoring his own writing over preaching from a pulpit.

Upon graduating from seminary and law school, Hopkins picked up his pen to become a reporter for a New York newspaper. He then continued his career as a scribe with the New York-based church journal. He was writing for the publication in 1857 when he confronted a special problem – the conundrum of what Epiphany gifts he should purchase for his brothers’ children. Ultimately, Hopkins decided to give a present that would both entertain and educate at the same time.

Having decided on his gift, Hopkins sat down at his desk with a single goal in mind: to write a moving tribute to the legendary visitors from the East described in the gospel of Matthew. To accomplish this mission, the writer imagined what it might have been like to be one of the wise men. A seminary graduate, he was aware that little was known about the travelers, so he combined the biblical record of the trip with the legers, so he combined the biblical record of the trip with the legends passed down over almost two thousand years.

Though largely a work of the imagination, the song that was produced as Hopkin’s gift to his nephews and nieces was instructive and worshipful. The cadence of his melody fully captured the image of a trip across the desert and plains on camels. The carol had an oriental, Middle Eastern feel to it and its rhythm reflected the beat of a march or the sway of a camel’s gait.

Hopkins’s words dramatically embraced the rich fabric of the trip, the gifts, and the birth of a Savior. Using simple, but inspired lyrics, the writer initially described the quest to find the king. Though the first verse contains only four short lines, they speak of a trip that was long and difficult: “bearing gifts we traverse afar.” The chorus, with its powerful view of a “star of wonder, star of light” guiding the wise men onward, provided the inspiration the men needed to not give up during the arduous and perilous journey.

The second verse begins the tale of a “king forever ceasing never” born in Bethlehem. Hopkins’s wise men realized that this king has not been born to rule a short time but for eternity. The composer therefore reveals that the three men were as wise as they were strong and courageous.

In the last part of the second verse and the following two stanzas the gift presented by the wise men are fully covered. Each gift is identified and the meaning of the gift told with almost biblical eloquence. The gold is the crown that the king would forever wear. The frankincense is there to help worship the Son of God. The myrrh is the bitter perfume that would mask death but then blossom forth in a life unending.

In the song’s final verse, Hopkins assures the youngest members of his family that the three wise kings knew that the Christ child would die for our sins and then be born again. In the last stanza, the writer reveals that to these three kins the journey was truly divine, worth every effort, and the most glorious moment of their lives. It not only defined their lives and purpose, it made them an important part of the most amazing story ever told.

Hopkins’s “We Three Kings of Orient Are” was published in the writer’s own songbook, Carols, Hymns, and Songs. At the turn of the next century, when many churches decided that carols should be included in hymnals, this musical work, which defined the reason for the celebration of Epiphany, became one of America’s most popular Christmas songs.

John Henry Hopkins Jr. never married or had a family of his own. Yet because he loved children, he’d be pleased to know that his most famous Christmas song is one of the most beloved children’s carols in the world. He probably wouldn’t even mind that on many occasions the lyrics to “We Three Kings of Orient Are” have been rewritten in several humorous ways.

What he would surely want every child to know is that Christmas gifts began not in a department store or a catalog but on the twelfth day of the first Christmas, when three men from the East brought gifts to the baby Jesus. Though many have now forgotten the celebration of Epiphany, John Henry Hopkins Jr.’s “We Three Kings of Orient Are” will never allow us to forget what the wise men brought to celebrate the birthday of the King of kings.